Allison David, Claymont Community Center CEO, and Joan Anderson, one of the 12 African American students admitted to Claymont High School in 1952, traveled to the White House to watch President Joe Biden sign the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site Expansion Act. Â

This innovative legislation creates multiple National Park Service (NPS) designations to help share the full history of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case, which led to the end of the “separate but equal†doctrine in public education and mandated the desegregation of public schools. Â

Claymont High School alumna Joan Anderson said, “Integration happened because everyone wanted it and worked toward it.â€Â  Â

“We have been working with the National Trust for Historic Preservation, along with many other people and organizations, for more than three years on this project. While there is so much divisiveness in our society today, I believe in my heart that finding common ground and working together are always possible,†said Allison David, Chief Executive Officer of the Claymont Community Center. “The spirit of Brown v. Board is alive and well today in the Claymont Community Center. We look forward to welcoming people to the Center to learn more about the Claymont’s role in the Civil Rights Movement and how the Center brings members of the community together today.â€Â

Creation and passage of the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site Expansion Act were led by House Majority Whip James Clyburn (D-SC) in the House and Senator Chris Coons (D-DE) in the Senate.Â

The 1954 Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court decision has been described by constitutional scholar Louis H. Pollak as “the most important American government act of any kind since the Emancipation Proclamation.†Brown v. Board overturned Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 ruling that established segregation through the doctrine of “separate but equal.â€Â Â

The history of Brown v. Board is currently represented in our national consciousness by a single building, Monroe School, which constitutes the National Park Service’s Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site located in Topeka, Kansas. However, Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia, and the District of Columbia had plaintiffs that were included in the Brown v. Board case. This legislation recognizes the contributions of all the communities involved in the case, conveying a more complete history of this pivotal moment in American history. Further, it connects communities representing plaintiffs in the landmark court case within the National Park System through the creation of NPS Affiliated Areas in Delaware, Virginia, and the District of Columbia and the expansion of the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka, Kansas to include related sites in South Carolina.Â

Claymont High School Integration – Key Dates and DetailsÂ

A story of bravery. A story of doing what’s right. A legacy for the community.Â

1950 – African American children from Claymont had to pass by Claymont High School on their way to attend Howard High School, the only high school in the State of Delaware open to African American students at the time.Â

July 1951 – Louis Redding, a prominent African American attorney in Delaware, filed a lawsuit seeking admission for a group of students after their parents consulted Mr. Redding for legal counsel. The complaint sought to challenge the notion of racially segregated public schools. The litigation used the name of one of the parents, Ethel Belton. The case named the State Board of Education as the principal defendant and the board members were specifically charged. The first name among the Board of Education members was Francis B. Gebhart, resulting in the first case filed as Belton v. Gebhart.Â

The local Claymont Public Schools Board knew that in order to integrate there would have to be a lawsuit. Virginia Tryon, the daughter of Sager Tryon, who was a member of the local School Board, recalls that her father and the others, wanted their community to integrate because it was simply the right thing to do. Everyone knew that this would mean a tough legal battle, but the parents and the school board bravely decided to move forward.Â

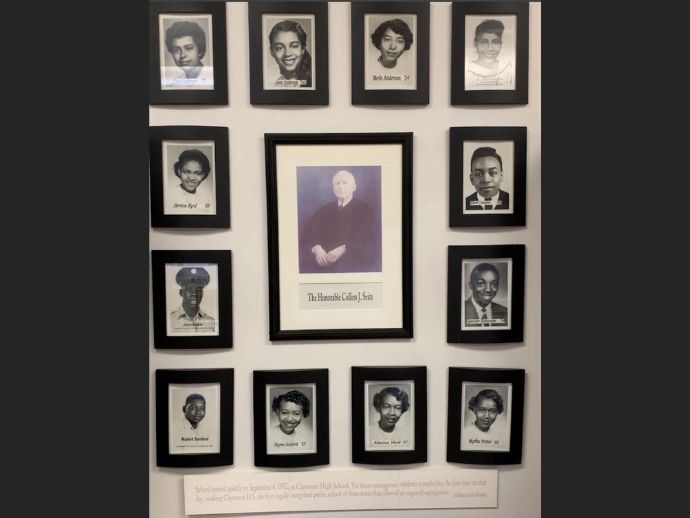

April 1952 – Chancellor Collins J. Seitz, presiding judge of the Delaware Court of Chancery, directed the immediate admittance of the African American plaintiffs’ children into Claymont High School. His decision was appealed but upheld by the Delaware Supreme Court in the same year. The Delaware decision offered that the doctrine of “separate but equal†was unconstitutional but only applied to the children of the plaintiffs named in the case. Broader application would come upon appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.Â

September 1952 – Claymont High School prepared to admit 12 African American students. On September 3, the local Claymont School Board called H. Albert Young, Attorney General of Delaware, every hour waiting for an official mandate. At a special late-night meeting, a call came from the Delaware State Board of Education giving the school verbal permission for the children to be enrolled. On September 4, the African American students attended the first day of school. On September 5, Attorney General Young called Claymont Public Schools Superintendent Henry Stahl, with instructions to send the children home because the case had been appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Stahl defied that order and allowed the children to stay at school. This was another example of everyday people simply doing the right thing.